Read more at https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/business/five-key-numbers-in-republican-us-tax-revamp-9511910

(Updated: )

Ricky Lim ·

US$1.456 TRILLION

The amount that the bill will add to the national debt between 2018 and 2027.

Even accounting for increased economic growth brought about by the tax overhaul, an approach known as dynamic scoring, the Joint Committee on Taxation projects the bill will cost about US$1 trillion over the next decade.

--

But US Treasury say :-

US Treasury says Senate tax plan would boost revenue US$1.8 trillion

Read more at https://www.channelnewsasia.com/.../us-treasury-says...

12 Dec 2017 01:14AM (Updated: 12 Dec 2017 01:20AM)

--

Is there a serious trust deficit - on what White House say & what Joint Committee on Taxation says.

More incline to believe what Joint Committee on Taxation say is true.

The amount that the bill will add to the national debt between 2018 and 2027.

Even accounting for increased economic growth brought about by the tax overhaul, an approach known as dynamic scoring, the Joint Committee on Taxation projects the bill will cost about US$1 trillion over the next decade.

--

But US Treasury say :-

US Treasury says Senate tax plan would boost revenue US$1.8 trillion

Read more at https://www.channelnewsasia.com/.../us-treasury-says...

12 Dec 2017 01:14AM (Updated: 12 Dec 2017 01:20AM)

--

Is there a serious trust deficit - on what White House say & what Joint Committee on Taxation says.

More incline to believe what Joint Committee on Taxation say is true.

Like · Reply · 1m

Ricky Lim ·

The World has to be careful toxic funds and toxic assets like those minibonds, Lehman Brothers etc that will be coming out few years down the road.

Banks must be careful not to carry such funds and assets, otherwise :-

(1) Ignorant public

(2) town councils

-- will get burnt by such funds like 10 years ago --- in which Obama has came out with banking regulations to stop.

But look like such banking regulations will be dismantle.

Banks must be careful not to carry such funds and assets, otherwise :-

(1) Ignorant public

(2) town councils

-- will get burnt by such funds like 10 years ago --- in which Obama has came out with banking regulations to stop.

But look like such banking regulations will be dismantle.

Like · Reply · 1m

Ricky Lim ·

The investment into BOA, Citibanks by Sovereign Funds also get hit 10 years ago.

Like · Reply · 1m

Ricky Lim ·

Otherwise how the debt is funded?

Like · Reply · 1m

Borrowing and the Federal Debt

Federal Budget 101

Deficit and Debt: What are they?

Why Does the Federal Government Borrow?

How Does the Federal Government Borrow?

Who Does the Federal Government Owe Money To?

Debt Held by the Public

The Debt Ceiling

Why Is There a Debt Ceiling?

The Great Federal Debt Debate

Endnotes

Borrowing and the Federal Debt

Federal Budget 101

If federal revenues and government spending are equal in a

given fiscal year, then the government has a balanced budget.

If revenues are greater than spending, the result is a surplus.

But if government spending is greater than tax collections, the result is a deficit.

The federal government then must borrow money to fund its deficit spending.

Deficit and Debt: What are they?

While

a deficit describes the relationship between spending and revenues in a single

year, the federal debt - also referred to as the national

debt - is the sum of all past deficits, minus the amount the federal government

has since repaid. Every year in which the government runs a deficit, the money

it borrows is added to the federal debt. If the government runs a surplus, it

can use the extra money to pay down some of its debt. And each year, the

government pays interest on the national debt as part of its overall spending.

As

of June 4, 2015, total U.S. debt stood at $18.153 trillion.

Why Does the Federal Government Borrow?

The

federal government has run a deficit in 45 out of the last 50 years. Usually

that deficit is around three percent of the economy, as measured by Gross

Domestic Product (GDP).

The

size of a budget deficit in any given year is determined by two

factors: the amount of money the government spends that year and the amount of revenues the government collects in taxes. Both

of these factors are affected by the state of the economy, as well as by the

tax and spending policies enacted by Congress.

For

example, during tough economic times like the Great Recession, many types of

government spending automatically increase because more people become eligible

for need-based programs like food stamps and unemployment benefits. At the same

time, tax revenues tend to decrease for a couple of reasons: people are working

less, and paying less in taxes; and corporations also earn less profit, and

they too pay less in taxes. What's more, lawmakers may intentionally increase

government spending during a recession in order to stimulate the economy, even

though they know that one short-term result will be a deficit. During the Great

Recession, the federal deficit in 2009 reached 9.8 percent of the economy, but

in 2015 is about average again, at 3.2 percent of the economy.

The

deficit can also reflect temporary spikes in spending that are not matched by

equal spikes in revenue (through increasing taxes, for instance). For example,

the deficit in 1943 at the height of war spending on World War II reached nearly

30 percent of the economy.

Finally,

tax policy plays a major role in determining whether we run surpluses or

deficits. Many factors probably contributed to the budget surpluses of the

1990s, but one of them was tax increases, which took the form of tax rate

increases for the highest income taxpayers (although rates stayed well below

what they had been prior to the 1980s). Likewise, major tax cuts in 2001 and

2003 were a major contributor to deficits over the last decade, and to today's

debt - by some measures, even more so than the economic downturn.

This

line chart shows the size of the deficit or surplus in each fiscal year over much of the

last century.

% of GDPAnnual Budget Deficit or

Surplus(1930-2015)193019401950196019701980199020002010-30%-20%-10%0%10%-40%

Source: OMB, National Priorities Project

How Does the Federal Government Borrow?

To

finance the debt,

the U.S. Treasury sells bonds and other types of securities (Securities is a

term for a variety of financial assets). Anyone can buy a bond or other

Treasury security directly from the Treasury through its website,

treasurydirect.gov, or from banks or brokers. When a person buys a Treasury

bond, she effectively loans money to the federal government in exchange for

repayment with interest at a later date.

Most

Treasury bonds give the investor - the person who buys the bond - a pre-determined

fixed interest rate. Generally, if you buy a bond, the price you pay is less

than what the bond is worth. That means you hold onto the bond until it

"matures." A bond is mature on the date at which it is worth its face

value. For example, you may buy a five-year $100 bond today and pay only $90.

Then you hold it for five years, at which time it is worth $100. You also can

sell the bond before it matures.

There

are actually many different kinds of Treasury bonds, but the common thread

between them is that they represent a loan to the Treasury, and therefore to

the U.S. government.

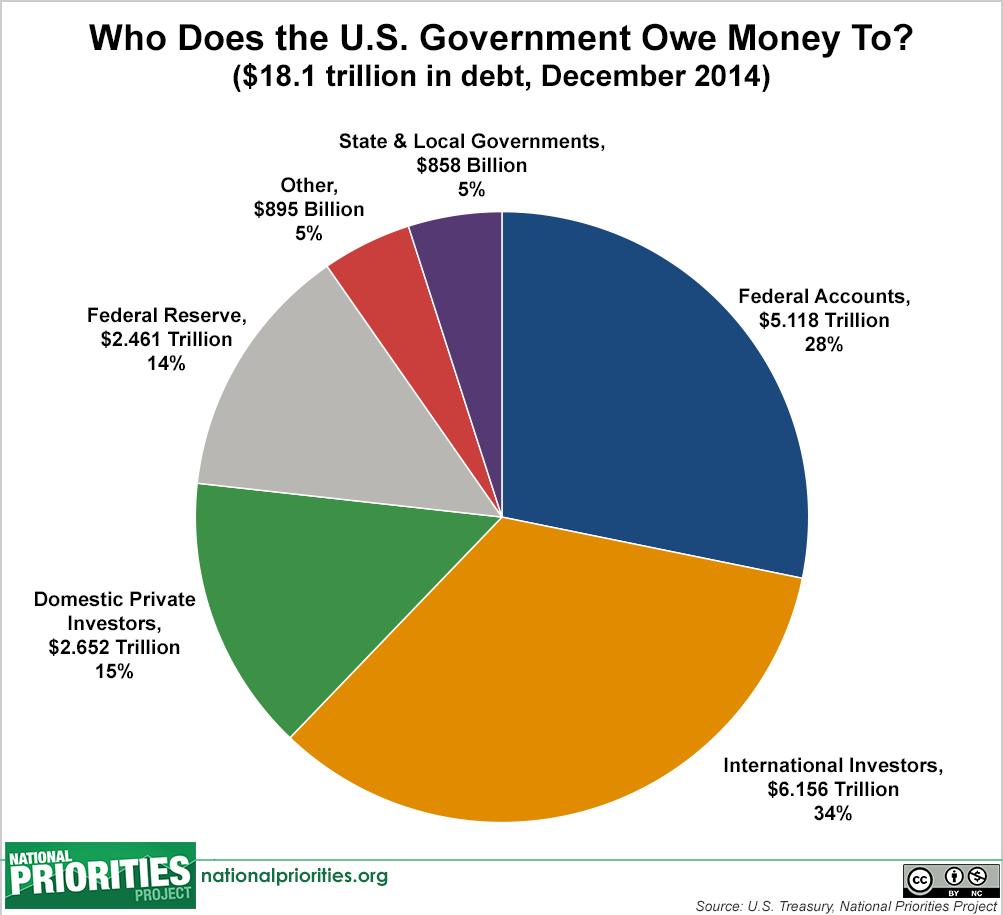

Who Does the Federal Government Owe Money To?

The

federal debt is the sum of the debt held by the

public - that's the money borrowed from regular people like you and from

foreign countries - plus the debt held by federal accounts.

Debt

held by federal accounts is the amount of money that the Treasury has borrowed

from itself. That may sound funny, but recall from Where the Money

Comes From that trust funds are federal tax revenues that can only be used for certain

programs. When trust fund accounts run a surplus,

the Treasury takes some of that surplus and uses it to pay for other kinds of

federal spending. But that means the Treasury must pay that borrowed money back

to the trust fund at a later date. That borrowed money is called "debt

held by federal accounts;" that's the money the Treasury effectively lends

between different federal government accounts. Almost one-third of the federal

debt is held by federal accounts, while the remaining two-thirds of the federal

debt is held by the public.

Federal AccountsInternational

InvestorsDomestic Private InvestorsFederal ReserveState and Local

GovernmentsOtherWho Does the U.S. Government Owe Money To?($18.1 trillion in

debt, December 2014)

Source: U.S. Treasury, National Priorities Project

Debt Held by the Public

Debt held by the public is the total amount

the government owes to all of its creditors in the general public, not

including its own federal government accounts. It includes debt held by

American citizens, banks and financial institutions as well as people in

foreign countries, foreign institutions and foreign governments.

As

you can see in the pie chart above, about one third of the total federal debt,

and nearly half of debt held by the public, is held internationally by foreign

investors and central banks of other countries who buy our Treasury bonds as

investments. These countries include China ($1.3 trillion), Japan ($1.2

trillion) and Brazil ($262 billion), the three countries that currently hold

the most U.S. debt. Treasury also groups foreign holders of national debt by

oil exporting nations (including Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Ecuador, Nigeria and

others, $297 billion) and Caribbean banking centers (Bermuda, Cayman Islands,

and others, $293 billion).3

The

next largest portion of debt held by the public is held by private domestic

investors, which includes regular Americans as well as institutions like

private banks.

The

U.S. Federal Reserve Bank and state and local governments also hold substantial

shares of federal debt held by the public. The Federal Reserve's share of the

federal debt is not counted as debt held by federal accounts, because the

Federal Reserve is considered independent of the federal government. The

Federal Reserve buys and sells Treasury bonds as part of its work to control

the money supply and set interest rates in the U.S. economy.

The Debt Ceiling

The debt ceiling is the legal limit set by Congress on

the total amount that the U.S. Treasury can borrow. If the level of federal

debt hits the debt ceiling, the government cannot legally borrow additional

funds until Congress raising the debt ceiling, and could be left with no way to

pay its bills. If this happens, it could result in sudden interruptions of

government services and unintended consequences.

Congress

has the legal authority to raise the debt ceiling as needed. Doing so does not

authorize new spending, but rather allows the Treasury to pay the bills for

spending that has already been authorized by Congress.

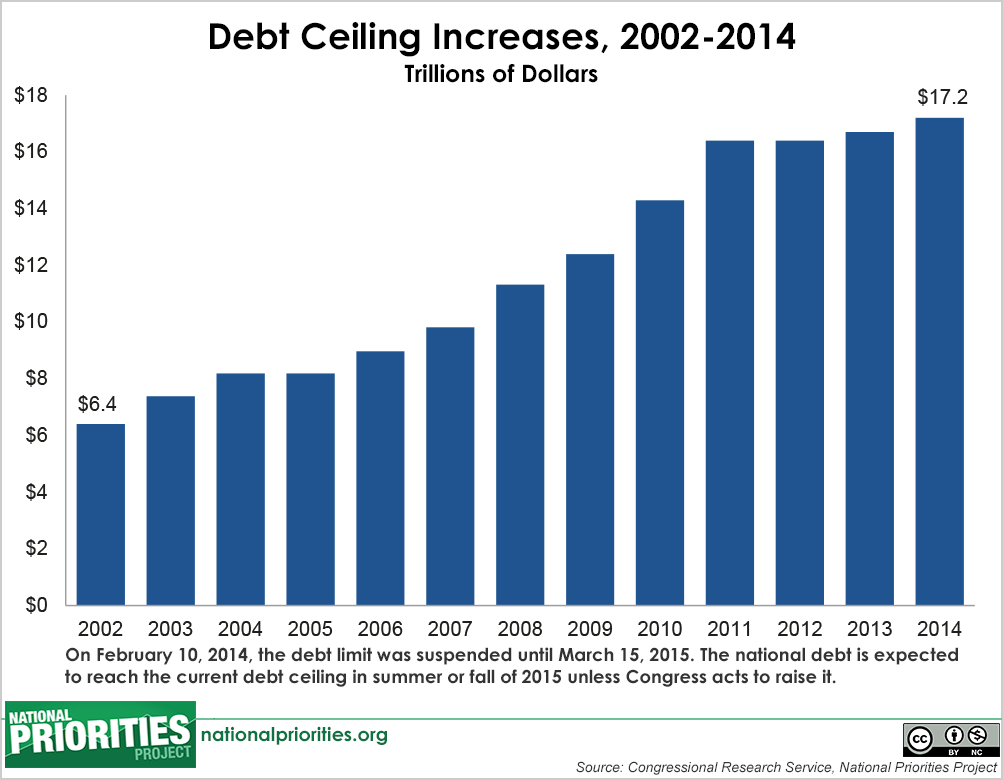

Why Is There a Debt Ceiling?

The debt ceiling evolved from restrictions that

Congress placed on federal debt nearly from the founding of the

country. Legislation that laid the groundwork for the current debt ceiling was

passed in 1917, and the first overall debt ceiling was passed in 1939. Since

then, the debt ceiling has been raised or otherwise amended more than 140

times, including more than a dozen times since 2000.

Debt Ceiling Increases, 2002-2014Trillions

of

Dollars2002200320042005200620072008200920102011201220132014$5$7.5$10$12.5$15$17.5$20

On February 10, 2014, the debt limit was suspended until March

15, 2015. The national debt is expected to reach the current debt ceiling

in the summer or fall of 2015 unless Congress acts to raise it.

Often,

the decision by Congress to raise the debt ceiling has not been controversial.

Since 2011, however, due to political partisanship as well as debates about the

size of the federal budget and deficit spending, the debt ceiling has become a

highly contentious issue. Some members of Congress have pledged to allow the

federal government to default on its debt payments rather than raise the debt

ceiling again.

The Great Federal Debt Debate

There

is an ongoing debate as to whether the government should limit its ability to

borrow. Some consider deficit spending to be a hindrance to the

government and the economy, arguing that a deficit only shifts the burden to

future generations because it must be paid for eventually, just like any other

loan.

Others

see deficits as a crucial way for the government to stimulate the economy

during an economic downturn. Proponents of this view believe that the role of

government is not only to provide services that the private sector won't, but

also to stimulate the economy during economic crises. They argue that deficits

are necessary in times of economic hardship, but that during economic booms,

budget surpluses should be used to pay down the debt.

In

some ways, deficits and debt are actually less controversial than you would

think from listening to the rhetoric - with deficits in 45 out of the last 50

years, our government has chosen policies that lead to slight deficits more

often than not, regardless of who controls Congress or the White House. And in

times of surplus, lawmakers across the political spectrum have argued to use

some of the surplus not just to pay down the debt, but for other priorities

like government services or tax cuts.

Endnotes

1.

U.S.

Department of Treasury, "Major Foreign Holders of Treasury

Securities." April 2015 <http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/data-chart-center/tic/Documents/mfh.txt>

No comments:

Post a Comment